The READ COMMITTED isolation level states that a transaction may only read data that has been committed in the database. There are no dirty reads. There may be nonrepeatable reads (i.e., rereads of the same row may return a different answer in the same transaction) and phantom reads (i.e., newly inserted and committed rows become visible to a query that were not visible earlier in the transaction). READ COMMITTED is perhaps the most commonly used isolation level in database applications everywhere, and it is the default mode for Oracle databases; it is rare to see a different isolation level used.

However, achieving READ COMMITTED isolation is not as cut and dried as it sounds. If you look at Table 7-1, it looks straightforward. Obviously, given the earlier rules, a query executed in any database using the READ COMMITTED isolation will behave in the same way, will it not? It will not. If you query multiple rows in a single statement, in almost every other database, READ COMMITTED isolation can be as bad as a dirty read, depending on the implementation.

In Oracle, using multiversioning and read-consistent queries, the answer we get from the ACCOUNTS query is the same in READ COMMITTED as it was in the READ UNCOMMITTED example. Oracle will reconstruct the modified data as it appeared when the query began, returning the answer that was in the database when the query started.

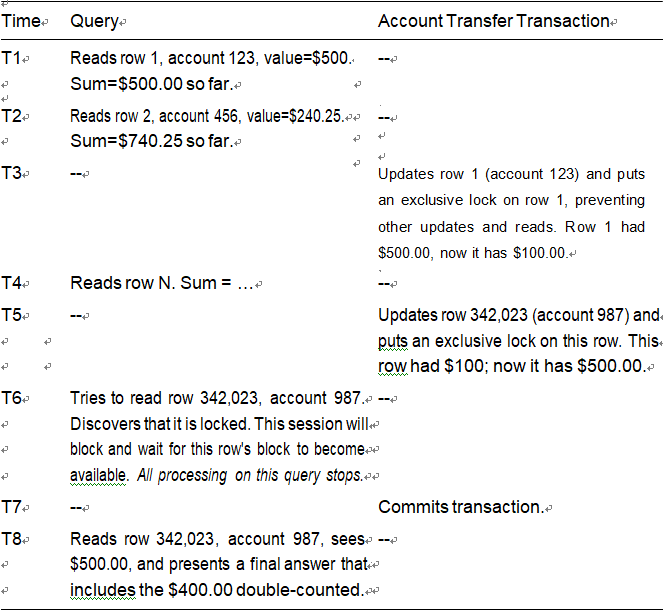

Let’s now take a look at how our previous example might work in READ COMMITTED mode in other databases—you might find the answer surprising. We’ll pick up our example at the point described in the previous table:

•\ We are in the middle of the table. We have read and summed the first N rows.

•\ The other transaction has moved $400.00 from account 123 to account 987.

•\ The transaction has not yet committed, so rows containing the information for accounts 123 and 987 are locked.

We know what happens in Oracle when it gets to account 987—it will read around the modified data, find out it should be $100.00, and complete. Table 7-4 shows how another database, running in some default READ COMMITTED mode, might arrive at the answer.

Table 7-4. Timeline in a Non-Oracle Database Using READ COMMITTED Isolation

The first thing to notice is that this other database, upon getting to account 987, will block our query. This session must wait on that row until the transaction holding the exclusive lock commits. This is one reason why many people have a bad habit of committing every statement, instead of processing well-formed transactions consisting of all of the statements needed to take the database from one consistent state to the next. Updates interfere with reads in most other databases. The really bad news in this scenario is that we are making the end user wait for the wrong answer. We still receive an answer that never existed in the committed database state at any point in time, as with the dirty read, but this time we made the user wait for the wrong answer. In the next section, we’ll look at what these other databases need to do to achieve read-consistent, correct results.

The important lesson here is that various databases executing in the same, apparently safe isolation level can and will return very different answers under the exact same circumstances. It is important to understand that, in Oracle, nonblocking reads are not had at the expense of correct answers. You can have your cake and eat it too, sometimes.